This impact story was originally published by the Earthworm Foundation here.

Over the past decade or so, I’ve frequented the Aceh region of Indonesia, initially as a social scientist conducting research in this area known for its primary forests and post-disaster reconstruction efforts. Aceh, situated in the northern part of Sumatra, has a tumultuous history marked by the pro-independence movement and subsequent conflict with Indonesian armed forces until a peace deal in 2005.

Additionally, the region faces the recurring threat of natural disasters, such as the devastating 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami. Despite these challenges, Aceh boasts some of Southeast Asia’s most biodiverse tropical forests and mineralized soil, attracting loggers and artisanal mining activities.

As part of an international research cluster, I investigated socio-economic factors driving informal gold and semi-precious gemstone mining in the forest periphery. Transitioning from urban research to this forest-dominated area, I quickly formed a profound connection with the forest, much like the local miners, loggers, and smallholders. Amidst the lush forests and stunning coastline, I witnessed a rural Aceh, in the case of the western part of Aceh I visited still transitioning to plantation agriculture on a small scale, devoid of large palm and pulp and paper estates.

Recently, I returned to Aceh and Riau, another province in Sumatra, this time amidst the palm oil and pulp and paper industry surge. The area had transformed drastically since my last visit, dominated by sprawling palm oil and pulp and paper plantations, yet pockets of untouched virgin forest remained.

Working for Earthworm Foundation, our focus lies in supporting the regeneration of key sourcing areas for commodities like palm oil and pulp and paper, essential for global brands and producer companies like Mars, Hershey, Nestlé and others. Earthworm’s Landscape work also focuses mainly on contributing to resolving the tension between commodity production, nature conservation, and community consciousness in Indonesia. It often seemed quite challenging to accomplish to me, but when my Indonesian colleagues recently took me to the location depicted in the photo below, within our Aceh Landscape, everything fell into place.

I took the picture last year during a field assignment, a kilometre from a palm oil plantation. The place is abundant with natural beauty – virgin forests and gorgeous waterfalls. It’s a postcard-like scenario and the good news – it’s all still there. It makes me believe that the trade-off between production and protection is possible.

After being inspired by the uplifting experience of visiting the waterfall and gaining insights from working with the Earthworm Indonesian team on local stakeholder empowerment and nature protection, I’ve compiled a series of key lessons I’d like to share.

Lessons from Indonesia

1. Modern models and tools exist to balance production and protection.

The landscape approach we implement at Earthworm Foundation is a good example of an approach that reconciles production, protection, and community respect. In its Indonesian landscapes in Aceh and Riau, it unites stakeholders across the palm and pulp&paper supply chains – smallholders, palm and wood growers, downstream buyers, and government bodies, especially at the district level – around common goals such as drastically regenerating soil, promoting ecosystems protection, and advocating community prosperity and human rights. Earthworm’s Landscape approach is rooted in grassroots efforts, integrating effective local solutions and prioritizing strategic collaborations with local stakeholders to ensure systemic effectiveness and progressively broaden the project’s impact.

All this is based on science and backed by facts: for instance, the health of ecosystems is monitored by satellites, in partnership with Airbus, while people-centered initiatives are guided by the latest trends in agronomy and social development. Additionally, Earthworm Foundation’s landscape interventions fully align with and contribute to the latest action plans being implemented by the Indonesian government to promote sustainable crop production, such as the Regional and National Action Plan for Sustainable Palm Oil.

2. One company can’t fix all the problems

Most actors understand that acting alone will not solve the problems in these sourcing regions. Companies that source from Aceh and Riau are beginning to realize that they must start to look beyond a single commodity, and single supply chain to have a tangible impact.

What amazes me about the landscape approach is the size of the impact that collective action can achieve by robust collaboration. Since 2021, the Earthworm-led landscape program in Aceh protected a total of 22,704 ha of forest inside and outside of concessions and helped almost 800 farmers to improve their livelihood. As for Riau, Earthworm Foundation and its partners are assisting 47 villages in completing Participatory Land Use Planning (a collaborative process where stakeholders develop plans to manage land resources) and agreeing on 687,401 ha of forest for protection, assisted 1,248 palm smallholders implementing good agriculture practices, and coached farmers’ groups to establish profitable business units. Find more about the Aceh and Riau projects’ progress.

And the best thing is that civil society organizations and local governments are generally welcome and increasingly see the benefits of landscape collective actions. This was the clear outcome I gathered from an informal discussion we had during my last visit to Riau between the different landscape players. The conversation was also an occasion to visit palm oil estates and farming training centers with the representatives of downstream companies that fund the landscape. For most of them, it was the first time they laid eye on actual palm despite working for a company that processes huge volumes of that commodity. Convening a landscape also means building a bridge between companies and producers and engaging them in candid conversations on challenges and solutions.

3. We can’t protect, conserve and regenerate our natural habitats if we don’t include communities and don’t have staff on the ground.

Local communities residing on the outskirts of forests have a vested interest in ecosystem health. Engaging them in decision-making cultivates a sense of ownership and responsibility. Collaborating with them to co-design strategies also enables the development of approaches that promote both forest preservation and sustainable livelihoods, while incorporating their local wisdom, traditional knowledge, and practices.

I’m an anthropologist by background and constantly keep an eye on human dynamics. When I was in Indonesia, before Earthworm, most of the people who went out to the mountains and looked for gold were young men who wanted to fund their marriages and put money aside to start a family.

In Earthworm’s program in Indonesia, farmers have nuanced access to the forest. In some cases, we work with communities that are directly connected to the forest; that live near the forest and are still tapping into the forest for income. And then another group of farmers, who have lost access to the forest, because there is little remaining or it’s too far away. What I observe is that farmers often struggle to make ends meet in a world where climate-change-fueled extreme events and ecosystem degradation are adding a strain on people.

One farmer who I met in Riau during my last visit inspired me immediately. In his mid-30s, he runs a newly constituted rice and crop farm together with his wife. His property borders a conserved forest plot, and pulp and paper growing areas. Running the farm and providing for his family is not easy because of the limited size of the farm and climate-induced agricultural shifts. Still, he’s eager to learn and adapt to new farming techniques to make his farm more productive and sustainable on an ecological and financial basis. His enthusiasm and openness to new things was a reminder to me that the coexistence of thriving forests and sustainable farming and smallholding is possible.

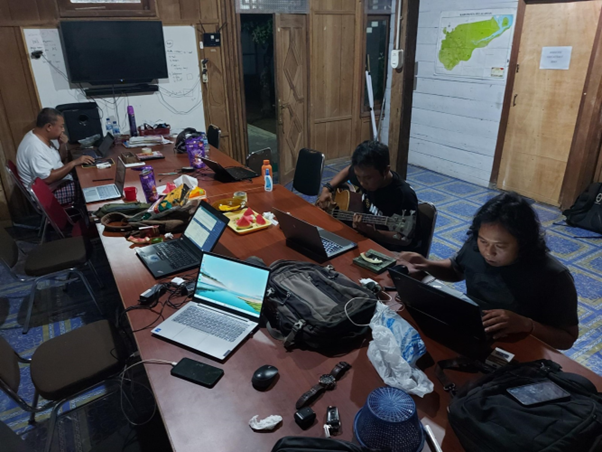

The heart of the project in Indonesia is to work with the communities to do land-use planning. To do so, we rely on rock-star fieldworkers on the ground whom I met during my stay and spent time with at our field houses. Their proximity to and empathy towards community members, no matter how remote their villages are, instantly reminded me of me in my late 20s during my research assignment in Aceh.

Back to our people-centered methodology. We study the area where the community lives, the village – the smallest unit of administrative framework. The field teams study the status of the land, which can include some forest, because often there are patches of forest within a village area. Then there are always other patches where there are already paddy fields, for example. So, it’s a patchwork of forests and some productive areas. Community involvement in the process is necessary to understand the local context better. What we do with land use planning is to reconcile the different statuses of the land – put it all together in the same document and agree with the community, landowners, local governments, and other land managers such as private companies on the status of the land.

The land-use planning is always the entry point. Based on that, we develop group of farmers such as cooperatives in targeted villages, which Earthworm coaches on farming. This includes good agricultural practices and all the techniques that will make farming more productive on the one side. On the other side, is also financial and marketing coaching. Meaning that we help farmers to sell their products and being economically stable, sustainable, and independent.

In Riau, one of the cooperatives we work with is well-trained and empowered and can already create a network of partner cooperatives. We see economic partnerships have formed, because they sell their product and buy fertilizers, farming tools, etc.

4. Impact on both people and nature grows deeper

What I’ve also come to understand is that landscape work is dynamic and evolves with time. As Earthworm and its partners continue to empower farmers, leverages the influence of producers to instigate changes in production, and supports local governments in sustainability efforts, the impact on both people and nature intensifies. In simpler terms, the transformation of value chains gradually takes effect, benefiting ecosystems, supply chains, and communities.

At the same time, Earthworm’s landscape-scale actions in Indonesia will mature, evolving to incorporate innovative collective efforts aimed at fostering people- and nature-positive sourcing regions for commodities. An authentic paradigm shift that I’m eager to see unfold together with my colleagues.

Big shoutout to my awesome Landscape and Communications team colleagues at Earthworm for all the help in putting together this blog and for sticking with me through this journey!