This impact story was originally published by UNDP here.

UNDP launches an innovative Guidebook to better understand the impact of landscape interventions, while increasing connectivity among stakeholders.

Alan Fox, Deputy Director of the Independent Evaluation Office (IEO) of UNDPA process that goes beyond a mere evaluative assessment and contributes to system-level learning, building capacity of implementing teams and increasing the chances of success.

In Peru we experienced CALI as a wonderful investment in learning.

Diana Rivera, Sustainable Productive Landscapes in the Peruvian Amazon Project Manager, UNDP

Reducing deforestation is vital for fighting climate change – the latest IPCC report[1] rated “reduced conversion of natural ecosystems” as the second largest potential contribution to emissions reduction by 2030, behind only increased solar power generation and even larger than wind energy.

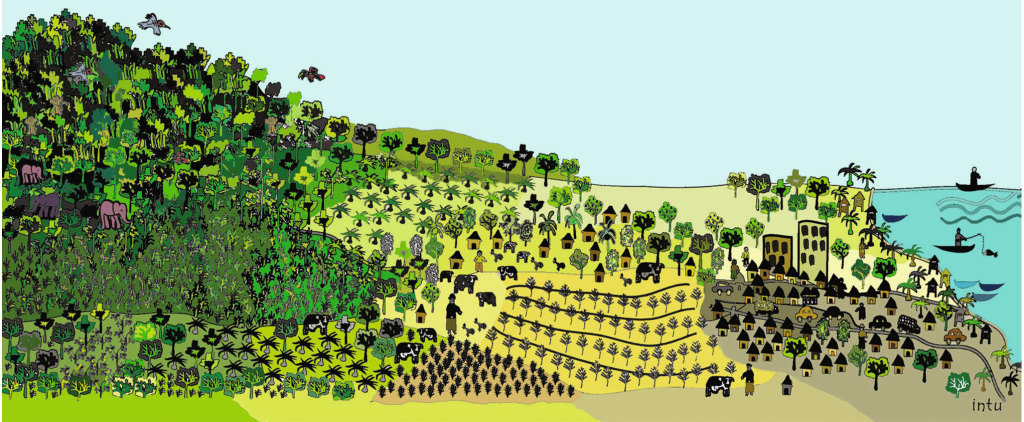

To reap these rewards we need to transform productive landscapes[2], complex systems shaped by the interplay of political, economic, social and natural forces. As with any intervention operating in complex systems, project teams implementing landscape approaches aiming to reduce deforestation at landscape level must be comfortable in dealing with uncertainty, while embracing emergence and continuous adaptation. The most effective way to do this is to place learning at the center of project interventions, so to inform sensemaking and regular adjustments. UNDP has just launched a comprehensive Guidebook full of advice and tools to achieve this.

As they developed UNDP’s CALI (Causality Assessment for Landscape Interventions) Guidebook, co-authors Andrew Bovarnick (Global Head of Food and Agricultural Commodity Systems) and Andrea Bina identified a series of limitations in the current “Business as Usual” approach to launching and managing development projects at landscape level, including a limited capacity to understand impact while unpacking a usually high number of critical assumptions. Because of the complexity of food systems – influenced by global and local shocks such as conflicts, climate change affecting yields, and varying economic pressures on farmers to name a few – it is very difficult to identify which changes result from a project and which are caused by external factors.

“Because project teams put together a series of proposed interventions and then implement them, it is just human nature to tend to only look for the results of what you have done yourself” commented Andrew Bovarnick. “It could be an external policy change, or a shift in commodity markets that caused the change, but if you are not looking at that broader context you will not get the full picture”.

So how do we do that in practice? How do we learn and adapt to complex systems when designing and implementing landscape approaches?

The new Causality Assessment for Landscape Interventions (CALI) Guidebook provides a practical methodology for ongoing sensemaking and adaptation for project teams and oversight to ensure effective and optimal implementation of project resources aimed to reduce deforestation in landscapes.

CALI works by bringing landscape stakeholders together in participatory reflections around the workings of the theory of change of the project – including through unpacking causality and examining the soundness of underlying assumptions – always remembering the context of the complex system which is driving deforestation in the landscape.

The assessment can be planned at project design or commissioned throughout implementation, and it can be conducted one or several times, depending on the length of the project and extent of changes in system dynamics.

Every assessment results in ideas for a refined theory of change and a strengthened project implementation strategy, that take into account emerging learnings and the latest evolutions of system dynamics. The project team has strong ownership of the process, which will help them better understand causality and the consequences (or not) of their actions.

Another key benefit is increased connectivity among landscape stakeholders – who are engaged in participatory sensemaking, and their understanding of system dynamics – as they are encouraged to “see the system” that drives deforestation in the landscape, as well as their role in it.

This puts the stakeholders in a better position to contribute to the development of the project’s interventions, as well as to more generally and effectively advocate for their interests, by adopting a system perspective. So we can say that CALI leverages the collective intelligence of landscape stakeholders to increase the chances of effectiveness of project interventions, but at the same time, it also contributes to enhancing that collective intelligence in first place.

The new Guidebook has been welcomed as a timely and critical innovation by Alan Fox, Director of the Independent Evaluation Office (IEO) of UNDP, and its latest application in Peru has been rated as highly successful by the local project team:

“We experienced CALI as a wonderful investment in learning, which will take you a long way to maximize your project impact. It is a practical methodology that guided us through an exciting journey to update our project’s theory of change, results framework and deliverables, following substantial changes in the drivers of deforestation in our landscape in the Peruvian Amazon.” Diana Rivera, Sustainable Productive Landscapes in the Peruvian Amazon Project Manager, UNDP.

The authors intend that the CALI Guidebook should become an essential tool for all donors and project teams to guide the wise use of essential resources through continuous learning and sensemaking. The Guidebook can be downloaded here.

To learn more on how the CALI methodology can be tailored to the uniqueness of your context, and how it can contribute to increase the effectiveness of your landscape interventions, check UNDP’s CALI tools page and do not hesitate to reach out to andrea.bina@undp.org.

[1] IPCC AR6 : https://report.ipcc.ch/ar6syr/pdf/IPCC_AR6_SYR_SPM.pdf

[2] A geographical space that results from the interaction between social, ecological, economic, and governability processes,[2] and is most commonly delineated around a specific ecosystem (or ecosystems) and/or delineated along jurisdictional boundaries.