This impact story was originally posted by Trase Insights here.

Many businesses are seeking clarity on how the EU deforestation regulation will be implemented, especially its proposed classification of countries by risk levels. The success of the law can be boosted by the EU closely engaging producing countries and using the best available deforestation data – including zooming in on regions within countries when considering risk.

The EU is finally passing its groundbreaking regulation requiring businesses to show that imports of agricultural commodities to the bloc are deforestation-free.

Estimates show agriculture drives over 90% of tropical deforestation ; deforestation and land use change, in turn, accounts for 11% of global carbon emissions . In richly forested Brazil, the share of national emissions from land use change is 46%. The climate crisis, therefore, cannot be resolved without tackling international commodity supply chains.

Now that the landmark law has been passed, it presents novel challenges. Exporting countries, businesses and environmentalists also want clarity on how due diligence requirements will work . The details of implementation are critical for the law to go beyond cleaning up European imports to effectively protect nature.

The High Risk Label

To ensure the law is successful, the European Commission must clarify how enforcement checks will rest on a fair, objective, data-driven framework. International discussions have featured doubt and confusion , with some describing the law as “protectionism” or “discrimination” against specific countries or commodities. Transparent communication and greater consultation with producing countries will be vital to defuse these perceptions.

The proposal to classify countries as “high,” “standard” or “low” risk has drawn particular concern . Imports from high-risk countries can enter the EU market, subject to the same due diligence requirements as those deemed a standard risk, but they face more intensive checks from enforcing bodies.

The largest and most forest-rich exporters are understandably unenthusiastic about potentially receiving a high-risk label and the reputational sting that comes with it. At the same time, these countries are those with whom the EU must urgently build a collaborative relationship to tackle deforestation.

Fortunately, improvements in deforestation data and sectoral methodologies offer promising ways forward. Data availability varies across countries and commodities but in developing its framework, the EU should not confine itself to “lowest common denominator” data sources, which have broad coverage at the expense of detail. Curbing deforestation effectively means using the best information wherever it is available.

Indeed, relatively detailed data, including crop and deforestation maps, cover some significant sectors, such as soy and beef in Brazil and palm oil in Indonesia. This high-quality information, including official statistics, reflects substantial investments in data transparency by producing countries themselves. The EU would benefit from consulting these states on incorporating these resources into its approach.

Discerning Deforestation Risk More Fairly

One especially fruitful route would be zooming in on regions within countries. The regulation provides for this possibility and it could answer many of the criticisms facing the law to date.

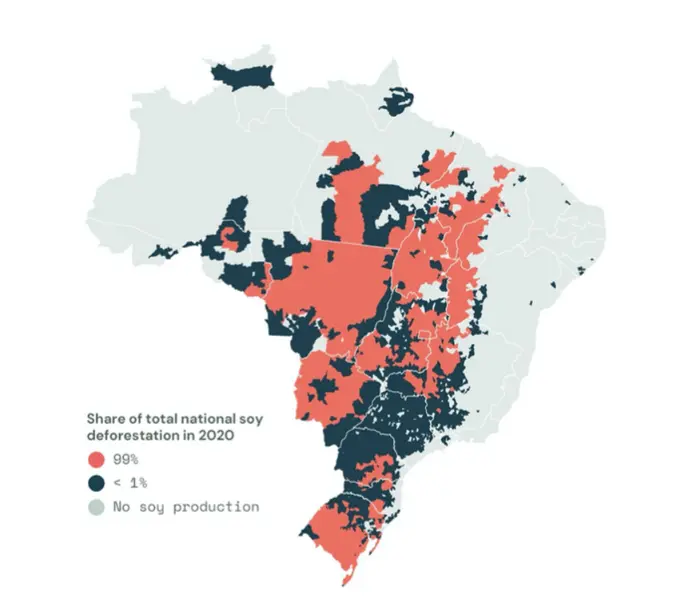

Advances in supply chain mapping reveal that even where a country presents a high risk overall, a large share of its production and many of its regions may reliably be classified as low risk. For example, when looking at soy production in Brazil in 2020, the transparency initiative Trase found that only 569 of around 2,400 soy-producing municipalities accounted for 99% of Brazil’s soy deforestation.

Where such data exists, in-country regions could be classified based on their percentage share of the national total of commodity-linked deforestation. For example, regions that together account for less than 1% of the national total could be classified as low risk. Compared to a system of blanket national risk levels, a larger proportion of trade flows could be subject to simplified disclosure requirements and less intensive enforcement checks.

This system would benefit businesses and regulators, bringing down compliance costs without compromising regulatory aims. This discerning approach could give the law more teeth. Ultimately, the regulation can only succeed with robust enforcement but enforcement agencies face the tough job of assessing huge volumes of information disclosed in a novel regulatory set-up. Nuanced risk classifications would help them devote more of their limited resources to the imports most urgently requiring scrutiny.

The EU could also make the classifications specific to particular commodities. An area which has seen recent intensive deforestation for beef, for example, could at the same time be a low-risk source for coffee. Recognizing the differences across sectors will avoid imposing burdens on companies already acting responsibly.

Critically, the classifications need to sit within a larger system of cooperation between the EU and producing countries. As discussions between the EU and South American Trade bloc Mercosur resume, these relationships may become even more critical. In addition to encouraging exchanges of data and expertise, the EU could make financial contributions to support the enforcement of land regulation or provide localized incentives for farmers in hotspots not to deforest.

The EU has correctly identified commodity deforestation as a shared problem, demanding solutions that span global supply chains. The costs of implementing those solutions likewise need to be equitably shared.