This impact story was originally published by HCV Network here.

About the jurisdiction

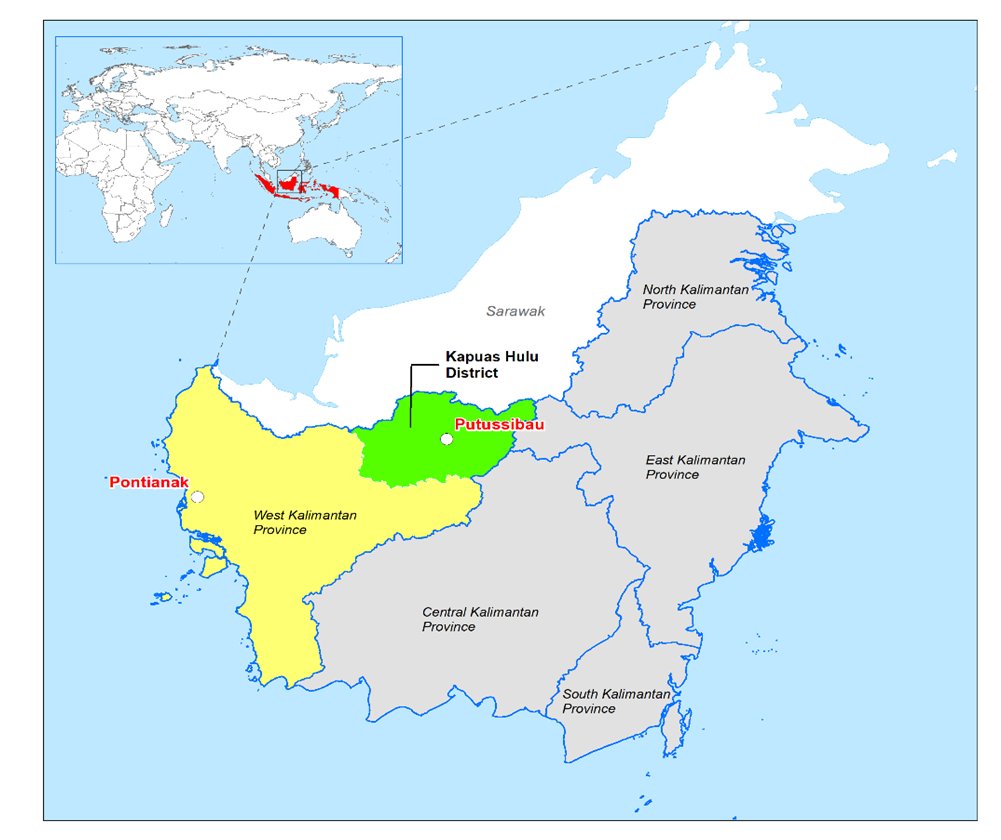

Over two million hectares of forest remain in Kapuas Hulu District, of which less than 40% is located inside National Parks. This means there is a significant amount of forest, supporting biodiversity conservation, ecosystem services and support for local livelihoods, that is potentially at risk.

In 2020 Kapuas Hulu became a member of the Sustainable District Association (LTKL in Bahasa Indonesia). LTKL is a collaboration forum of District Governments and development partners committed to green growth objectives and sustainable development.

The German Development Cooperation collaborated with the Kapuas Hulu District government to implement a jurisdictional approach to sustainable supply chains and economic development while minimizing the risk of deforestation and destruction of biodiversity and habitats. The Initiative for Sustainable Agricultural Supply Chains supports work on deforestation-free and sustainable supply chains for agricultural commodities such as oil palm and rubber.

Key facts:

- Area: 29,842 km2

- UNESCO Biosphere Reserve

- Member of LTKL (Sustainable Jurisdiction Network of Indonesia)

A practical example – HCV-HCS Screening implementation in Kapuas Hulu, West Kalimantan

Objective

The German Development Cooperation commissioned a jurisdictional screening for Kapuas Hulu District, in collaboration with the Kapuas Hulu government, to identify and address risks to sustainability in the landscape.

The objective of the screening was to understand where High Conservation Values (HCV) and High Carbon Stock (HCS) forests are situated, what the likely threats are to these areas, and which of these areas are most at risk. The focus was on the APL areas – or zones outside the state forest areas where commodity production is occurring and may expand.

Joint HCV and HCS screenings (i.e., large-scale indicative mapping)

The HCV and HCS approaches are often used together to identify areas important for conservation and livelihoods. Coordinating the use of both approaches brings efficiencies (e.g., when data can contribute to both HCV and HCS forest identification results and stakeholder consultation can be done simultaneously). By using both approaches together in landscapes and jurisdictions companies, conservationists, and other stakeholders can aim to identify and conserve more of the potential values present. Joint screening considers the likelihood that values are present, conducts indicative mapping and information gathering. It then analyses the possible threats to those HCVs and HCS forest and provides results to spark discussion, make recommendations and prioritize actions.

The work involved

HCV Network led a team of experts from Daemeter Consulting and Tropenbos Indonesia to conduct an HCV-HCS screening exercise to characterize the environmental and social aspects of the jurisdiction.

The screening results included indicative maps, a report, a short film and compiled information. These results were presented to stakeholders through a series of virtual workshops.

For the social HCVs (5-6) emphasis was placed on generating descriptive information on social HCVs and risks and gathering recommendations for next steps.

Key findings

Indicative maps of environmental HCVs (1-4) and HCS forests show that these conservation features cover most of the district with high degrees of overlap. HCVs and HCS forests are most at risk in areas that are allocated to agricultural land use and production forest.

Environmental HCVs in Kapuas Hulu include habitats for threatened species like the orangutan, peatlands, several types of forests, wetlands and peat swamps, habitat corridors, and critical ecosystems that provide services such as natural fire breaks and flooding controls.

Due to the high forest dependency of communities, all of Kapuas Hulu district is likely to have social HCV values, and although there are several threats, the impacts of oil palm development figures as the most frequently cited high-impact threat. An FPIC (Free, Prior and Informed Consent) process is essential to validate the indicative social HCV map and to build on the report findings.

What next?

The screening results provided important information for district spatial planning, for meeting the district’s sustainability objectives, and for sustainable sourcing and initiatives for rubber and oil palm farmers.

The screening results (and underlying data) can be used to support BAPPEDA and other government departments:

- in the preparation of future jurisdictional sustainability reports,

- for spatial planning,

- for regional development plans (RPJMD) and the Strategic Environmental Assessment,

- as a member of the Lingkar Temu Kabupaten Lestari (LTKL–Sustainable District Association) to design the development scenario portfolio following the regional competitive framework (KDSD),

- for the allocation of concessions such as oil palm, mining, etc.

One key recommendation is that there needs to be a coordinated approach that engages with government, private sector, NGO and community actors in the district. This is necessary to define the conservation and development objectives and to determine strategies and responsibilities necessary to achieve these objectives. Examples of these objectives are the allocation of oil palm concessions, requirements for plantation-level safeguards, participatory mapping and recognition of customary rights, and habitat restoration.

To learn more about this case study, HCV screening and learning opportunities, or to collaborate with the HCVN Secretariat, contact secretariat@hcvnetwork.org