Duration of engagment

Medium (1-3 years)

Cost

($)

Participant

($$)

Convener/Coordinator, requiring significant investments of staff time and travel

($$$)

Funder of third-party implementers

($$$$)

Implementer of one or more steps articulated through the land use planning process

In the real world

Mapping priority conservation areas in Côte d’Ivoire

The French chocolate manufacturer Cémoi co-funded and coordinated implementation of a land use planning program in the regions of Mé, Agnéby-Tiassa, and Indénié-Djuablin. The company partnered with Côte d’Ivoire’s Coffee-Cacao Council (a government agency responsible for regulating and developing the coffee and cocoa sectors), other funders, and technical service providers to develop a land use reference map by identifying High Carbon Stock and High Conservation Value areas and to identify and validate key areas to conserve through a process that obtains communities’ free, prior, and informed consent. With this mapping, partners were able implement a range of protection, restoration, and sustainable cocoa cultivation activities aligned with a spatially explicit land use plan.

Conservation planning from below

In the Kapuas Hulu district of West Kalimantan, Indonesia, Golden Agri-Resources (GAR) manages three plantations covering 20,000 ha, which overlap 14 village boundaries. GAR had made a commitment to implement the High Carbon Stock Approach (HCSA) methodology for halting deforestation. That meant reserving certain portions of its plantations for conservation. The company had to ensure that local communities would not deforest lands it would set aside and leave intact, but early efforts did not adequately engage local communities, who viewed the set-asides as land grabs. Following an independent review of the social impacts of the company’s forest conservation policy, GAR piloted a Participative Conservation Planning tool with The Forest Trust, village leaders, government agencies, and local NGOs. The tool combined conservation mapping with participatory village mapping, and identified which area to protect, to manage for local livelihoods, and to develop for industrial agriculture. GAR then shared these maps with local governments to inform village-level spatial plans that clarified and secured broad public support for clear land use determinations. To scale mapping and spatial planning, GIZ, the High Conservation Value Resource Network and the district government are conducting a High Conservation Value and High Carbon Stock assessment throughout the entire district.

Villages help decree wildlife migration corridors

Bumitama Agri is a large Indonesian palm oil producer that suffered a period of tensions with local communities in its concession area. In response, the company worked with IDH and Aidenvironment to adopt village-level land use planning, empowering local stakeholders to influence decision making and reduce future risk of conflict. This participatory approach with community members sets out to map current land use for production, protection, and infrastructure/housing, as well as to propose improved land use zoning. All this is then brought to the local government for formal approval, through a village spatial plan decree. Since 2016, the project has established participatory land use maps for eight villages. The different village-level plans are aggregated into defined zones that protect wildlife migration corridors in West Kalimantan that connect the Gunung Tarak protected forest with the Sungai Putri peat swamp forest. Beyond social and ecological benefits, Bumitama saw a clear business case for undertaking this work.

Key points for companies

Government entities have lead authority over land use planning, yet companies play an important role (see Annex 2 in the PDF version of this Guidance for further details). They may catalyze the public process if plans are absent or need updating, and they may participate in a process that the government has already initiated. Specifically, companies can:

Facilitate participation by relevant stakeholders in the planning process where these stakeholders are receptive and where the company possesses sufficient influence and trust to invite their participation. A neutral, third-party facilitator is often best positioned to convene diverse local stakeholders, including those who may not trust companies or other actors, and can mitigate the power imbalance between various interests.

Support development of a land use reference map that is produced in an inclusive, participatory fashion. A company may take on this work directly or support it by funding consultants or NGOs to lead the technical effort, while also providing data and staff time to help review documents.

- A reference map helps planners grasp how different actors are using a jurisdiction’s land. Stakeholders can identify overlaps with priority conservation areas, anticipate and defuse potential conflicts, and find alignments among productive uses and users.

Contribute staff knowledge, data, and ecological training to help determine priority areas for conservation in the landscape/jurisdiction.

- The technical process of prioritization – often led by a government entity or a third party – applies tools that delineate which areas require protection, restoration, or specialized management to achieve conservation outcomes (including High Carbon Stock, High Conservation Value, and Key Biodiversity Area methodologies). It also assesses overlapping land ownership, usage rights, and other social factors.

- GAR’s experience shows how companies (or governments, for that matter) cannot undertake land use planning without consulting affected populations, even where the intent (e.g. preventing deforestation) is virtuous.

Negotiate the land use plan in good faith, aligning corporate sustainability ambitions with job creation and social equity (empower the voices of local communities, smallholders, and women in the negotiation), while minimizing production-protection trade-offs.

External conditions that improve likelihood of success

- Stakeholders in the L/JI are willing to engage in the land use planning process based on shared interests in improving conservation while meeting economic needs.

- Government actors with land use authority demonstrate both commitment and capacity to use the resulting plan as the basis for regulation and enforcement.

- Land use experts are available who can identify and map priority conservation areas, and then integrate economic, environmental, and community perspectives into the plan.

- Local communities and smallholders have enough time and organizational capacity to participate through trusted leaders and chosen representatives.

- Land tenure had been clearly defined, and there is either an absence of, or a pathway for addressing, any conflicting land use rights.

- There is participation, or at least buy-in, by a critical mass of companies whose operations have significant impacts on land, ensuring accurate information and adequate support for the land use priorities and plan that emerges.

The business case for this intervention

- By working with relevant stakeholders to generate a land use plan, a company reduces risk of conflict over misaligned objectives, avoids potential duplication of activities and investments, and clarifies the government’s expectations of what companies can do to ensure their actions comply with the law.

- By aligning with the government and local stakeholders on permitted land uses, a company reduces risk that (in)action by others will undermine its own sustainability goals and targets.

- By embedding methodologies like the High Carbon Stock Approach or High Conservation Value assessments into landscape/jurisdiction-level land use plans, a company:

- Avoids the need to undertake conservation planning whenever it wishes to expand production or sourcing within the landscape/jurisdiction.

- Helps address deforestation on community-controlled forests both inside and outside the boundaries of its own managed farms or those from which it sources.

Duration of engagment

Medium (1-3 years)

Cost

($-$$)

Staff time/flights to participate in meetings/provide comments to written materials

($)

Support for meeting costs or to fund participation by local stakeholders

($$-$$$)

Consultants to assist with initiative design and facilitation

In the real world

“Hotspot Intervention Areas” reduce emissions

The Ghana Cocoa Forest REDD+ Program (GCFRP) aims to reduce emissions driven by agriculture expansion, secure Ghana’s forests, and improve incomes and livelihood opportunities for farmers and forest users. The nation’s Forestry Commission has established a results-based planning and implementation framework through which the government, businesses, civil society, traditional authorities, and local communities can collaborate. The GCFRP has identified nine priority “Hotspot Intervention Areas” (HIA) in which local public and private stakeholders jointly design and implement scaled interventions.

a. In the Asunafo-Asutifi HIA, for example, 8 cocoa companies have been working with facilitation from Proforest and the World Cocoa Foundation on landscape-level assessments to support development of a management and investment plan.

b. Across other HIAs in Ghana’s larger Juabeso-Bia landscape, an initiative known as the Partnership for Productivity, Protection, and Resilience in Cocoa Landscapes (3PRCL) seeks to remediate deforestation caused by cocoa farming and other activities. Working with key stakeholders (cocoa producers, traders, processors, chocolatiers, logging companies, civil society, and government), the agro-industrial company, Touton, co-led a multi-year process to develop 3PRCL, creating a joint governance structure, goals, and strategies that would improve cocoa farmer yields and reduce deforestation. Through this process, stakeholders in each HIA created local natural resource management bodies, each empowered to register more than 5,000 farms illegally located in forest reserves, then help traditional and governmental authorities remediate the farms’ impacts over a 25-year period. The initiative has closely aligned its goals and strategies with the GCFRP and will test the standard and certification system for ‘climate-smart cocoa’ emerging under Ghana’s Cocoa Board.

Pursuing total statewide certification

In the state of Sabah, Malaysia, the Jurisdictional Certification Steering Committee (JCSC) oversees development and implementation of a work plan for achieving the goal of 100% statewide certification to the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) standard. The JCSC is a multi-stakeholder group whose representatives — from government (5 departments), private sector (5 companies), and civil society (5 NGOs) — collaborated to develop a 5-year action plan to achieve Sabah’s certification. HSBC, Sime Darby, Wilmar, and two local companies participated in this process.

Crafting local sustainability metrics

Leaders of districts with membership in the Sustainable Districts Association (LTKL) have agreed to a set of credible targets and a reporting system aimed at boosting competitiveness and attracting new investment based on each district’s demonstrated sustainability. The districts worked with 31 companies through LTKL’s Partners Network to formulate the Kerangka Daya Saing Daerah (KDSD)/Regional Competitiveness Framework. KDSD integrates national policies and market-based frameworks (SDGs, Principles & Criteria of the RSPO, Terpercaya, Sustainable Landscapes Rating Tool, and Verified Sourcing Areas) for sustainable commodities production, ensuring coherence with subnational policy. Agribusinesses in each district are helping collect relevant data and translate the KDSD framework into locally specific targets, sustainable production plans, and means of verification. For instance, district-level translation of the framework in Siak, in Riau Province, is being done by a group of companies that includes Cargill, Danone, GAR, Musim Mas, Neste, PepsiCo, Unilever, RAPP, APP, and Chevron, with facilitation by Proforest and Daemeter.

Co-writing a road map to reach the “Green District”

In 2016, Indonesia’s Siak District in Riau Province set out with ambitions to become a “Green District.” A coalition of eight companies (Cargill, Danone, Musim Mas, Nestlé, PepsiCo, Golden Agri-Resources, Unilever, and L’Oréal) convened with facilitation from Daemeter and Proforest to help implement the district’s ambitious sustainability policies. These companies worked closely with the Siak government, the NGO coalition Sedagho Siak, and the community collective Kito Siak to develop a road map that would support the transformation toward sustainable palm oil across the district.

Key points for companies

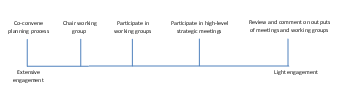

To shape a L/JI, a government agency or NGO typically convenes a multi-stakeholder group to develop goals, KPIs, and implementation strategies (companies should see Annex 1 in the PDF version of this Guidance for further details of this process). The company’s role is to bring its perspective to discussions and help find solutions that boost productivity while minimizing negative environmental impacts and ensure respect for human rights. As illustrated here, a company’s level of engagement may vary based on its specific goals and level of investment (and/or risks) in each geography.

Companies should:

Clarify multi-stakeholder process goals and roles: who will participate, what they will contribute, and how the process it envisions will unfold.

Carefully consider whether all key stakeholders are represented (both those who can influence and achieve goals, and those most affected by their success or failure). If any appear to be “missing”, figure out how to recruit them, either from the start or at a later date if more appropriate.

During a multi-stakeholder process, communicate and negotiate in a constructive manner through an approach based on shared interests.

Identify information and resources to bring to the table and seek complementary inputs from other participants. For example, companies can help document and visualize data, yet ensure that subsequent planning and decision-making processes (using those data as a guide) are both inclusive and highly participatory.

Identify information and resources to bring to the table and seek complementary inputs from other participants. For example, companies can help document and visualize data, yet ensure that subsequent planning and decision-making processes (using those data as a guide) are both inclusive and highly participatory.

External conditions that improve likelihood of success

- Stakeholder interests are sufficiently complementary and/or aligned to develop shared goals and plans for the L/JI

- Local government is committed to progress toward sustainable practices

- A multi-stakeholder body represents the key actors in the landscape/jurisdiction

- That multi-stakeholder group has enough upfront funding to convene and start discussions

- There’s an adequate baseline for legal enforcement and relative lack of corruption

- Skilled facilitation (often by a neutral third party) is available to help build trust and find common ground

The business case for this intervention

- By aligning jurisdictional goals and KPIs with its own sustainability objectives, a company can leverage multi-stakeholder efforts to deliver outcomes it needs to deliver anyway (e.g. mapping of no-go areas, reduced illegality, verified conversion-free supply).

- Dialogue with relevant public agencies as part of the co-design process presents an opportunity to advocate and/or develop solutions to deforestation that minimize the regulatory burden and associated costs.

- Getting involved in the design process can provide a more transparent, affordable, and secure way for companies to voice opinions and indirectly shape local policy than by more directly advocating with government officials.

- Direct engagement with relevant agencies, CSOs, and communities can build relationships that prove valuable in other ways (e.g. being consulted on relevant decisions, familiarity with suppliers and their challenges/priorities).